If you eat grains and follow an ancestral diet, you’ll probably have heard that we should soak our grains (or flour) in water and an acidic medium before cooking. This process not only softens and hydrates the grain, but it also helps neutralise ‘anti-nutrients’ that can bind to minerals and therefore stop you absorbing them.

Phytic acid is perhaps the most well-known of these mineral-stealing ‘anti-nutrients’. It’s possible to neutralise the damage that phytic acid potentially does by activating another compound that is naturally-present in grains: phytase. Phytase is an enzyme in grains which breaks down the chemical structure of phytic acid and stops it doing its potentially damaging work.

Hence one of the tenets of ancestral cooking: soak your grains. This action helps activate phytase allowing it to break down phytic acid, meaning you don’t have to worry about not absorbing the minerals in your meal.

What’s different about oats?

This logic, although sound for most grains, doesn’t extend to oats for two reasons:

- Oats are naturally low in phytase.

- Virtually all oats are processed in a kiln before they get to us. This action most likely destroys phytase.

So, soaking oats in water and an acidic medium doesn’t help when it comes to inactivating phytic acid; there’s no phytase in the oats to act as a catalyst. Soaking oats like this will soften them which is beneficial. If you add a live starter to the soaking water you’re going a step further – studies have shown that both lactic acid bacteria and yeasts have the ability to break down phytic acid but importantly, the starter does not provide phytase, the enzyme that is known to break down phytic acid .

The standard answer

The standard answer to this dilemma is to add in a grain that is high in phytase (like rye) to your soaking medium. I have followed this advice for years, using my wholegrain rye sourdough starter when I soak my oats.

And I would have continued this way, had I not delved deeply into oat and grain science for the book on oats I’m currently researching. The piecing together of information from many scientific papers has led me to understand that the method that I’ve been using for over a decade (of adding rye sourdough starter) is not ideal either.

Here’s why:

As soon as grains are ground into flour, the enzymes in them are exposed to oxygen and start to degrade. This includes phytase. So, if you’re using anything other than a high phytase grain that’s been freshly-ground, it’s probable that there’s no phytase in your flour.

In order to do our best to potentially inactivate the mineral-stealing phytic acid we need to include a high phytase flour such as rye (or buckwheat) with our soaking oats AND that flour needs to be freshly-ground.

Learning this information is part of the reason why I now have a Mockmill electric grain grinder on my kitchen counter. I freshly-grind a handful of rye berries every time I soak oats for my morning oatmeal.

If you’d like to know how I do it, check out this post; The Best Way to Soak Oats.

If you want to hear more about this topic, you can listen to Ancestral Kitchen Podcast #70 – Fermenting Oats

The last word: As far as I can see, no-one has done a direct study on this – actually setting a scenario with freshly-ground flour and then measuring subsequent phytase levels, but the conclusions are clearly deducible from information in grain studies. (If you want to have a look yourself, read the words and quoted studies on the comments of this post (many thanks to Richard!))

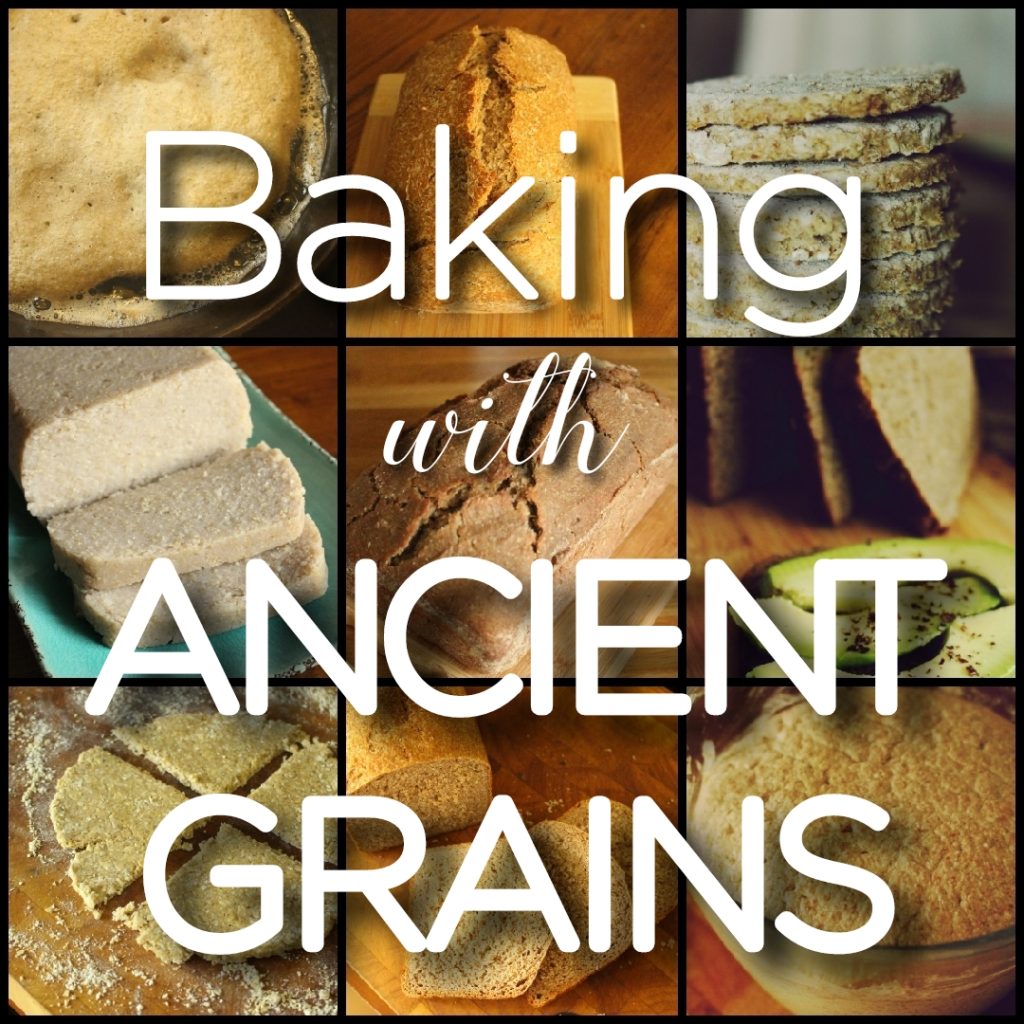

Bring ancient grain baking into your kitchen!

Download my free 30-page guide with five healthy and tasty 100% ancient grains recipes.

Do I need to soak my oats overnight and rinse them The next morning to eliminate or reduce phytates?

Hi Scott. There is no need to rinse the oats after soaking. If you read my post The Best Way To Soak Oats here: https://ancestralkitchen.com/2023/11/14/the-best-way-to-soak-oats/ I detail my method. I hope this helps.

Kristina, looks like you might be the one to not understand the article.

There’s a difference between phytase, and phytate.

Phytates are the bad things.

It is the phytase that oats are low in to start with, and the kiln process destroys the majority of whatever phytase is left.

Did you not read the article Scott? By the time we get oats they are usually dried in a kiln which eliminates it.

The article refers to phytase (the enzyme which breaks down phytic acid) being broken down in the Kiln, not phytic acid which is what Scott is asking about.

When you say a handful, about how much rye do you mean? With how much oat? Steel cut, whole oats or rolled?

Can buckwheat groans (unroasted) be used instead. This grinds in a blender, whereas rye does not.

How finely does the rye or buckwheat need to be ground? How long and st what temp soak? I can’t usually manage 65 degrees, but 68 winter and 75 summer works.

Would millet work? Quinoa? High enough in phytase? Taste better with oats in my opinion. Does taking certain strains of probiotics help? Cooking the oats with dried fruit/ apples, prunes, cranberries, figs?

The quantities I use are in this post: https://ancestralkitchen.com/2023/11/14/the-best-way-to-soak-oats/

I use rolled oats.

Yes, you can use buckwheat. I would grind as finely as possible (as long as you can do this without overheating it).

I would soak overnight and warm, if you can. The more you can create a good environment for phytase, the better.

I wouldn’t use millet or quinoa. They don’t have enough phytase.

I have not come across any studies showing probiotics help and dried fruit doesn’t contain phytase, so wouldn’t help with this particular issue.

Would purchasing sprouted oats eliminate the need for soaking?

I would feel happier eating sprouted oats regularly than unsoaked, unsprouted oats. I like what the sprouting process enables. However, I don’t think there’s been much conclusive research on sprouting oats and phytic acid. I’ve read one source saying it didn’t help, others saying it does help.

Phytic acid’s role is to help prevent sprouting out-of-season, so when a grain is sprouted the phytase is of course neutralized.The sprout is the proof that the physic acid is broken down.

Thank you Maureen! Since writing this response I’ve read more on germination and agree that phytic acid is neutralised upon germination. It’s little help in the average kitchen though as the majority of oats are kilned therefore won’t sprout. Even the raw naked oats I’ve found this year haven’t sprouted.

I have had issues with grains/legumes most of my life. At this point, I’m also off brassicas. However, Oats have different botanical properties than most grains and I’ve not experienced a problem with them. But I have found issues with low iron even though I eat meat and milk daily. We’ve sourced the problem to phytic acid. I don’t really like oat meal, so I’ve started making my own dehydrated oats. But I’m finding just soaking in water, cider vinegar and salt for 24 hours, then leaving to dry at 50-60c results in a starchy oat which I don’t like the taste of. On the other hand, soaking in whole milk + yogurt in the fridge for 24 hours, then dehydrating for another 24 tastes far better. Is the milk process pointless? It softens in the cool, then ‘soaks’ while drying. I do add salt and sometimes half a lemon to the warming process. Also, will milling walnut into the warm process help? These are a staple.

The oats themselves, if not raw, won’t have any phytase in them, so unless you introduce phytase to the soak, you won’t be activating the process that breaks down phytic acid. Milk and yogurt don’t contain phytase, so my educated guess would be that you are not affecting phtyic acid content. Have you noticed any difference to your iron levels since switching to your soaking method? Do you have access to a grain mill? If so, and you can get rye berries, I suggest you try that.

I’m coeliac, so I cannot consume rye. And finding the right oats feels near impossible. The only ones I can find are Soma GF jumbo oats. I’ve really only just found out about soaking in the last few years, as well (though incorrect). I love granola, but companies have been getting ‘creative’ with it and adding things in I cannot digest like Fructo-oligosaccharides or rapeseed oil (mustard/brassica) and so on. So, I started making my own.

Only lately, they’ve not been turning out right. I’ve also just found out they can affect Amylase. And have noticed a difficulty with starches since eating oats near-daily. I could probably use help! Nourishing traditions has just arrived – it’s a bit overwhelming. Perhaps, if you’re ever available for a consultation, please get in touch! x

Can you buy oatgroats and roll them yourself? They taste much better that way, and are cheaper. I have a post on it here: https://ancestralkitchen.com/2024/05/14/three-reasons-to-roll-your-own-oats-how-to-do-it/#:~:text=If%20you%20roll%20your%20oats,to%20shop%2Dbought%20rolled%20oats.

Buckwheat is high in phytase and gluten-free, can youuse that instead of rye?

I have two podcasts on Nourishing Traditions. If you fancy a listen, check the Ancestral Kitchen Podcast feed. It might help you feel less overwhelmed.

I am not absolutely sure but I think I read that vitamin C also breaks down phytic acid. So I make sure I add fruit and or take vit C in the morning with my oats.

Yes, you are right. Vitamin C mitigate has been shown to help iron absorption.

Hi Alison,

I purchased these raw oats (never heat processed) and wonder if that would do the trick so that I could leave out the fresh ground flour. (At least until I can buy a mill.)

Thanks for all the helpful information!

Julie

Raw Whole Grain Rolled Oats – 5 lb. bag

Hi Julie,

There are two issues that need consideration with these oats.

Firstly, as soon as oats are ground/rolled the enzyme lipase in them begins to degrade their fats. I’ve read varying reports on how long this takes to happen – from a few days to number of months, and I expect it depends on storage conditions. I see that the company that sells these recommend that they are kept in the freezer. This would slow down the degradation of the fats and therefore enable the oats to keep longer. Although they say that the oats are milled in small batches in Texas, it isn’t clear how long they have been in the packaging before they come to you.

Secondly, to the phytic acid/phytase issue: phytase, which can degrade phytic acid is also an enzyme. This means that as soon as an oat is rolled (and therefore its insides exposed oxygen) phytase is degrading. Therefore it could well be that by the time you get to soaking them for your morning porridge, whether or not they’ve been stored in the freezer, there’s no phytase left to help degrade phytic acid. There have been no controlled experiments on this that I can find so is very hard to be 100% sure.

The un-heat-treated oats will be much tastier and, of course, everything is better less processed, so I have no doubt they will be more nutritious than heat-treated oats.

If you aren’t ready to buy a grain mill yet, another option could be for you to buy these same oats but in the whole groat form. Without exposure to oxygen this type would have its phytase still intact. You could then buy a roller to roll them one batch at a time. Mockmill do an electronic version which is cheaper than their grain mill. You can find the details here: https://ancestralkitchen.com/2024/05/14/three-reasons-to-roll-your-own-oats-how-to-do-it/ There are also hand grain flakers available.

Perhaps not the answer you wanted, but I hope it helps!

Thanks for the tip. However, there is another very easy way to circumvent the “problem” with phytic acid (there are now also several studies ascribing a positive effect of phytic acid for cancer prevention):

Add something rich in Vitamin C to your meal. Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C) strongly decreases the “anti-nutriant” effects of phytic acid:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31119995/

So, just adding some fresh fruit should also do the trick.

Thanks Felix.

I agree that phytic acid has been shown to have positive benefits. That’s why, in my podcast about fermenting oats (https://ancestralkitchenpodcast.com/2023/11/70-fermenting-oats/), I said ‘don’t panic’…it’s potentially only one meal a day for most and there are potential upsides.

I knew about the vitamin c potential, but had not seen this study. Thanks for sending it over. I think this is a major reason why the Scots did not exhibit nutrient deficiency whilst subsisting on oats…they had freshly-picked vegetables and berries.

dear Ali

thank you for your article and answering our questions. it is so very informative!

I want to make my own toasted muslie and lower the phytic acid content in the oats first.

Do you have a recipe that does this?

I am thinking that if I soak rolled oats with freshly blented buckwheat groats the whole thing might turn into sludge. I was wondering, could soak whole oat groats with whole buckwheat groats, then dry/cook them… would this reduce the phytic acid?

thank you for your time and knowledge 🙏

Hi Angela,

I don’t think soaking whole oats and whole buckwheat would work. The grains need to be milled in order for the phytic acid/phytase reaction to work.

The best way I can think of making muesli with lowered phytic acid content oats would be to soak the rolled oats with a live starter plus freshly ground buckwheat/rye flour and then dehydrate/dry them before using in the muesli.

I hope this helps!

Thank you so much for this interesting information. I was trying to make oat milk, using sprouted oats. Nearly all the recipes I’ve encountered tell me not to soak them overnight. Is there any way to make an oat milk that has fewest phytates? Unfortunately I have to limit dairy, even the raw, fermented kind.

This is a very good question. There is no way I know of to deactivate phytic acid without soaking broken-down (ie rolled or cut) oats or sprouting. I have made oat milk myself by soaking the whole groats (it’s not the same consistency as store-bought milk) but without grinding the oats beforehand or sprouting the grains they phytic acid is still there.

I am writing a book on oats and will probably get to experimenting more with this, but I’m not there yet.

Whereabout in the world are you? Where did you get your sproutable oats?

Thanks! I’ve always wondered about phytates in nut and oat milks. I live in Ontario, Canada and my sprouted oats come from Costco. The brand is One Degree. They’re not sproutable, merely sprouted

I think phytates are ignored in processed ‘milk’ products. Thanks for letting me know about the sprouted oats! I guess you could make your own oat milk from those.

Okay, since i know myself, i would end up going down the rabbit hole. What is by your current knowledge the best way to remove the phytic acid?

I would buy whole grain oats right?

next i would grind them? (or sprout before and dry grind them after) – or is here the very problem already, that whole grain oats are already loose in what is needed for the whole process to work.

the gears in my mind that are grinding to find reliable information, could grind me a whole month worth of oats just like that.

I much rather ask someone who at least went in some tunnels of the rabbit hole to tell me where i don’t even have to search because it would end in a dead-end.

thanks for providing this information

Hi Jan,

Yes, standard whole oat groats have already lost any phytase they had.

This article explains my thoughts on the best way, whether you grind your own or by pre-ground/rolled: https://ancestralkitchen.com/2023/11/14/the-best-way-to-soak-oats/

It is to my understanding that phytates are highest in the bran of the oat (based on a Google search and unless you tell me otherwise)… So can we buy bran-free oat flour? Do you know of a brand?

I see that companies sell “oat bran”. In which case it’s a process where they remove the bran off the oat groat and package the removed bran… But do they ever make flour with the portion of the remaining oat that doesn’t contain bran?

I see the potential to buy “whole oat flour”, but that I presume that contains the bran. It’s like I’m looking for “white” bran-free flour!

You are right that the phytates are in the bran.

There is conflicting information online about whether oat flour contains the bran. I don’t use it so have never investigated. My advice would be to contact the mill/company you potentially buy from and get them to confirm.

What if we’re gluten-free so we can’t use rye. I still want the benefits of eating oats.

You can use buckwheat instead of rye.

I want to make granola, do I need to soak my fresh oats first? or will baking my oats get rid of the phytic acid? I love having granola with my yogurt in the morning! Thanks!!!

Baking oats will not remove anti-nutrients. If you want to do this, soak you oats as per my instructions before you bake them.

Hi, can I boil my 1 cup of rolled oats in about two quarts of water and then drain off most of the water when nearly done? Would this reduce anti-nutrients?

Boiling on it’s own won’t reduce the anti-nutrients. You need to pre-soak the grains.

Thank you, one last question. If I soak oatmeal overnight in the refrigerator phytase enzymes are activated. They reduce phytates to phosphorus and minerals will be better absorbed. Why then cannot I not re-heat the oatmeal? I read phytase survives to 175°F and about 135°F still active. But why not just go ahead and boil it, as the phytic acid has been changed to a harmless substance? I must be missing something?

For best results soak the uncooked oat in a warmer environment than the fridge, phytase activates best at higher temperatures. At that point you can boil the oats, yes, as the phytic acid has been neutralised.

I’m sold. I will enroll in your sourdough rye starter course. Can you recommend where to buy rye berries, or maybe you sell them? I have a small spice grinder about the size of a 16ounce glass for water. can I use this? grind size is a function if the amount of time actually grinding

Whereabouts in the world are you? I’m in the UK. I don’t sell grains but you can look for a local mill or use somewhere like Grand Teton (if you’re in the US) or Glichesters (if you’re in the UK). Your spice grinder might do the job, but grains are tough and I wouldn’t want you to break it. I use a Mockmill. You can read about why (and find suppliers) here: https://ancestralkitchen.com/2023/10/11/want-to-freshly-grind-grains-for-bread/

Brouns F. Phytic Acid and Whole Grains for Health Controversy. Nutrients. 2021 Dec 22;14(1):25. doi: 10.3390/nu14010025. PMID: 35010899; PMCID: PMC8746346.

Searching, I found this. Possible might give you places to research yourself for the combination and fermentation of grains?

Hi Alison, thanks for you great info on oats and phytic acid. I wonder if you have any info on making Oat milk. From the little research I’ve done, they discourage soaking any longer than 2 hours, as it makes the milk slimy. Any thoughts on this.

This is a great question and one I will get into experimenting with more as I flesh out my book. For the moment, I can make non-slimy oat milk with a 24 hour soak no problems. The key is to strain it through very fine cheesecloth so that the larger starch particles don’t come through.

Thanks so much Alison. Several of the posts online say NOT to strain it through cheesecloth, but to use a metal strainer instead, and to NOT press down. From what I gather the longer you soak it the slimier it gets, which is why they recommend only doing it for a maximum of 2 hours, but as we both know this is not long enough to deal with the anti nutrient problem. So I wonder if you also avoid pressing it out of the cheesecloth, or do you just let whatever go through, go through and discard the rest… or use it in a smoothy.

At the moment I go easy on the cheese cloth. I don’t press or squeeze it, but I do gently stir the mix (I rest the cheesecloth in a sieve) to remove the bits that cake the bottom of it and stop the liquidy bits going through. I then let the liquid that collects in my jar under the sieve sit for at least 12 hours. When I am ready to drink it, I pour gently so that any remaining bits stay at the bottom of the jar do not come into the milk. I then usually add this ‘bottom sand’ to my porridge.

Ali,

I have been fermenting my sprouted rolled oats that I have in my pantry (using live kefir) for my daughter and I to eat for breakfast. After reading these comments I am slightly disheveled. If my oats are sprouted, are they low in phytic acid? Should I also be adding rye or buckwheat to introduce the phytase? I am trying my best to make sure my family and I are getting the most nutrients out of our meals! I have learned so much from you so far thank you for sharing all your knowledge!

Hi Isabell,

My understanding is that sprouted oats should be low in phytic acid, as the sprouting process breaks phytic acid down. I haven’t personally seen any studies that confirm this though. I think by buying sprouted oats and then fermenting them, you are doing a great job of avoiding phytic acid. I don’t think you need to add the freshly-ground flour unless it’s an easy thing for you to do.