Lardo, the traditional Italian way of dry curing pork fat, is a delicious. It is best sliced very thinly and can be eaten in many ways.

Here are some favourite ways to enjoy it:

- Lay lardo on top of warm crunchy sourdough toast

- Top home-made pizza with lardo and fresh rosemary

- Wrap a date or an almond in a fresh, wafer-thin slice of lardo

- Place slices of lardo on or around just-cooked vegetables, on top of mushrooms or wrapped around asparagus so they begin to melt

- Melt lardo slices in the cast iron pan and cook vegetables or an omelette in the fat

- Crisp slices up on the stove, pour the released fat over your food and enjoy the crunchy, salty remains

The ‘original’ lardo is Lardo di Colonnata. Colonnata is a tiny hill-top town in Tucany that is famous for its marble quarrying. It is said to be the place where Michelangelo got his raw material! The local marble has, for many centuries, been used to make large basins in which pork fat would sit, covered in salt and herbs, for months, slowly transforming.

You can replicate Lardo at home, without needing the marble basins. Neither do need a place to hang the cure – a fridge will do fine. It’ll take several (completely hands off) months, but it’s completely worth it! Here’s how:

Ingredients:

- A 1kg piece of fresh, high-quality pork fat, rind still on, ideally around 3cm thick

- 250g coarse sea salt

- 15g black peppercorns

- 8 large or c. 12 medium garlic cloves

- c. 8g fresh rosemary (this is about 4 sprigs)

- 4-5 bay leaves

- 20g fresh, or 10g dried, juniper berries

(You can use other herbs; sage and thyme also work. You can also mix spices like coriander and cumin into your cure.)

Equipment:

- Something to wrap the cure-covered fat in. I use several large pieces of parchment/baking paper secured with elastic bands, but you could also use a large zip-lock plastic bag

- Something to cover the curing fat in when refrigerating to keep out light. I use several dish towels, but a large black plastic sack would work too.

- Something to weigh the fat down with whilst it’s in the fridge. I use three empty olive oil bottles, filled with water.

- A space in your fridge that you can spare for several months. I use part of the meat drawer.

Method:

- Clean the pork fat with water and pat dry.

- Prepare the herbs: Mince the garlic very finely, chop the rosemary and bay, crack the peppercorns and smash the juniper berries.

- Mix the salt with the prepared herbs.

- Place the pork fat on or in the medium you will cover it in – i.e the parchment paper or the ziplock bag – and rub the cure onto its surface really well. Use all of the cure and work on getting it to adhere to the fat. The whole of the area needs covering for good results.

- When you are happy that you’ve covered the whole surface, secure the wrapping. When using parchment paper I usually wrap the fat well with the original piece and then place it on another piece and wrap that at 90 degrees to the original piece before securing it with two elastic bands. If you’re using a ziplock bag, squeeze the air out and press the sides to the fat before sealing.

- Wrap this parcel in something to keep out light – several dish towels or a black bag.

- Place the covered lardo in your fridge in a spot where it won’t be disturbed. Weigh it down by placing something heavy (I use water-filled olive oil bottles) on top of it.

- Wait. How long you wait is up to you and something you will learn your personal preference for over multiple lardo-making sessions. Most people say three to six months. I have left lardo two months with success and also four months. It’s strong enough for me like this. I haven’t gone the full six months yet!

When it’s done:

When you are ready to eat, remove from the fridge, unwrap and dust off the cure into your sink/a bowl. Although here in Italy, you can buy lardo with a crusting of cure still attached, at this point I tend to go further and wash off the remaining cure, patting dry the lardo. I do this as I find it too salty otherwise.

How to cut:

With the lardo rind-side down, slice it as thinly as you can stopping your knife when you hit the rind. Continue until you have as many slices as you require. Then turn your knife so it is horizontal and free these slices from the rind by cutting across the fat, just above the rind.

Traditionally the exposed rind is then folded back onto the fat (but it’s always been to solid for me to be able to do this!).

How to store:

Store, kept in the original or a newly-created wrapping in the meat drawer of your fridge. It’ll last for months and months like this. When you’ve enjoyed it all, use the remaining rind with strong scissors and use it to flavour a pot of soup!

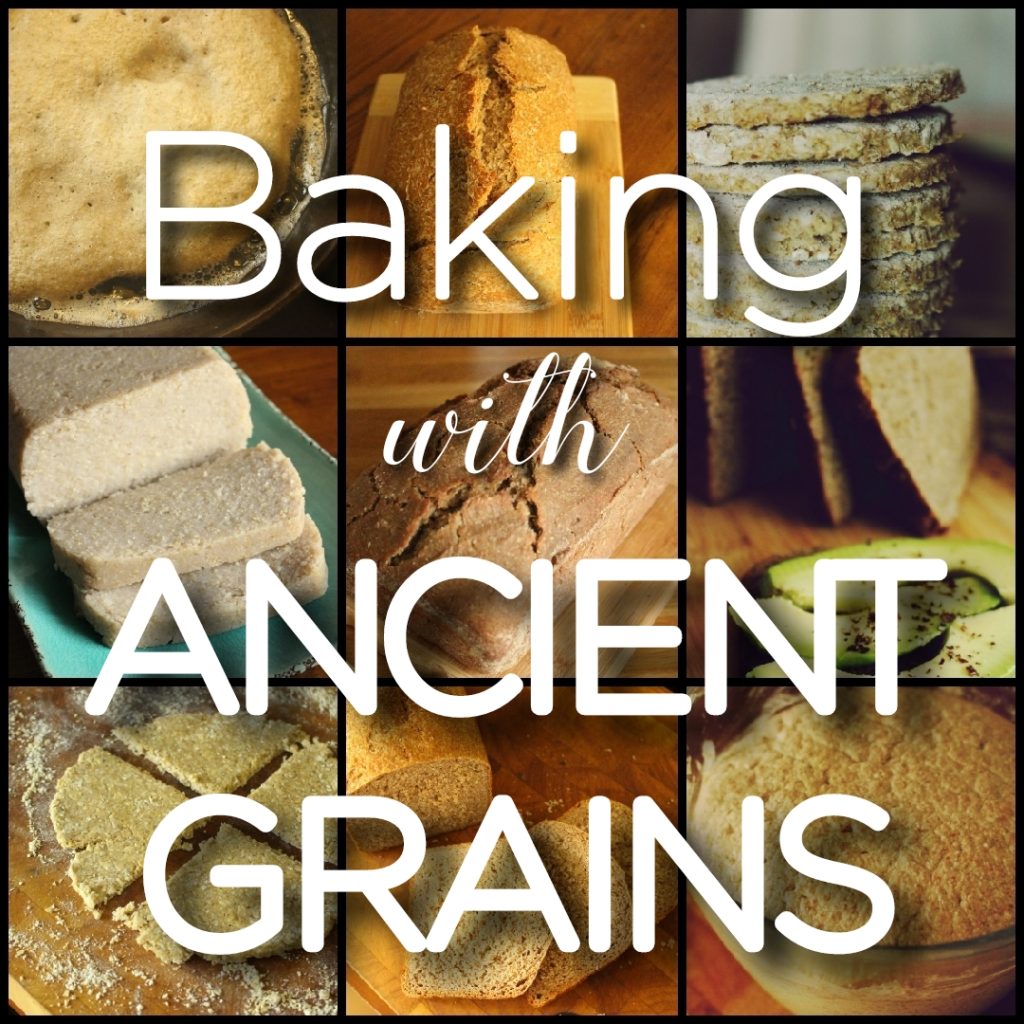

Bring ancient grain baking into your kitchen!

Download my free 30-page guide with five healthy and tasty 100% ancient grains recipes.

Hi! I love your website complete with information about ancestral foods and diets and the immense benefits of fermented and preserved food as well as the historical angle to them. I am in NYC, and I have worked with chefs and farmers throughout my career. I have always been drawn to the stories of culture and cuisine, and I am currently working with my business partner to start a market called ‘Lardo’ with the mission of ‘Preserving culture through food’. Where are you based? I would love to connect and pick your brain on your relationship with ancestral foods and also tap into your communities.

Hi Shaina. I currently live in Italy. I have a podcast with nearly 70 episodes on ancestral eating. You should start with those. The podcast has a patreon community if you want to dive deeper. Thanks,

Alison

I have never had Lardo but it sounds amazing and delicious, and am so glad I found this page. I will be making it soon, so I can see what it is all about. I also plan to look for the real thing at some Italian markets in philly soon so I know what it’s supposed to be.

Anyway my question is why do you have to weight it down, is the pressure necessary to force the salt and seasoning into the fat? And does that mean the weight needs to cover the entire thing.

Thanks

Hi Adam. I hope you can find some in Philly. The pressure mimics the traditional force that would have been applied in marble vats here in Italy. I think it keeps the cure in contact and helps make the product more dense. I don’t have mine covering completely all of it (I use two/three olive oil bottles with water in them) but I’d say a good 70% is covered. Hope this helps!

Hi! I have back fat but it doesn’t have skin or rind on.. could I try this still?

I’ve never made (or seen) it without the rind, but I’m not actually sure what the rind does…so I think you could give it a go!