I grew up with porridge (what us Brits call oatmeal). My steaming bowl of breakfast, made with rolled oats, warmed many a dark morning. As a child, I thought this was hearty British food, and was completely unaware that oats came in any other form than rolled…let alone that my Scottish ancestors never traditionally made their porridge with rolled oats.

Several decades on, I am still an oat-lover (in fact, I’m such a fan that I’m currently writing a book on traditional British uses of them). But if you look in my kitchen now, you’ll find many more types of oats than just my childhood rolled ones.

Several decades on, I am still an oat-lover (in fact, I’m such a fan that I’m currently writing a book on traditional British uses of them). But if you look in my kitchen now, you’ll find many more types of oats than just my childhood rolled ones.

The choice on our shelves these days can be bewildering – groats, rolled, thick, old-fashioned, quick, instant, oatmeal, pinhead, steel-cut, sprouted, black and naked. This article is a comprehensive guide to the types of oats available, how they’ve been processed and how to use each type the traditional way.

What are oats?

Almost all of the oats you’ll find in kitchens throughout the world are seeds of the grass genus Avena Sativa. These grow covered by a hard, inedible hull which has to be removed before the seed can be used as a grain. The hull adheres strongly to the seed and in the process of removing it the grain is very often damaged and exposed to the air. This activates an enzyme called lipase which degrades the fats in the oats causing them to go rancid, giving them a bitter taste. To avoid this happening, oat grains are ‘stabilised’ (heat and steam treated) at the very early stages of processing.

Almost all of the oats you’ll find in kitchens throughout the world are seeds of the grass genus Avena Sativa. These grow covered by a hard, inedible hull which has to be removed before the seed can be used as a grain. The hull adheres strongly to the seed and in the process of removing it the grain is very often damaged and exposed to the air. This activates an enzyme called lipase which degrades the fats in the oats causing them to go rancid, giving them a bitter taste. To avoid this happening, oat grains are ‘stabilised’ (heat and steam treated) at the very early stages of processing.

Most of the oats we buy are already ‘cooked’

This stablilsation means that the oats that make it to our kitchens (unless they are naked or sprouted oats) have been ‘cooked’ using a mix of heat and moisture (at an average temperature of 90-100°C).

Once the dehulling and stabilisation has been completed, oats are processed in a number of ways. This article explains what you might see at your mill or supplier, sorted from the least-processed to the most-processed:

Types of oats, how they’ve been processed and how to use each the traditional way

Oat groats

These are whole, unground, uncut oat grain. As they are whole grains, they take the longest to cook of any oat.

These weren’t often traditionally-used for porridge (though our ancestors in the UK did use the for savoury ‘puddings’), but I think they are great cooked this way.

These weren’t often traditionally-used for porridge (though our ancestors in the UK did use the for savoury ‘puddings’), but I think they are great cooked this way.

If you want to use oat groats for porridge/oatmeal, cook them as an alternative to rice or add them to a stew, I suggest soaking them overnight in water. The next day, drain and rinse them, before cooking for at least 35 minutes. For a cup of soaked groats, you’ll need around 3 cups of liquid (broth is a great savoury choice instead of water here!)

Stone-milled oats:

The only way of making the whole oat grains into smaller pieces, more suitable for cooking, until well into the 1900s was to process the grains in stone mill. This created a meal (rather than the more commonly found rolled oats we see today). This meal is what our European oat eating ancestors (who didn’t have rolled oats) would have eaten.

Why Our Scottish Ancestors Didn’t Eat Rolled Oats (link to article)

Stone milled oats are still available, though can be harder to source outside of the UK. They come in three grades:

Pinhead oatmeal

Oat groats ground between two millstones set very widely apart to break the groat into a few pieces.

This was traditionally used for porridge (oatmeal), particularly in Ireland.

To make a traditional pinhead oatmeal porridge, soak the oatmeal in water overnight using one part oatmeal to four parts water by weight (you can add a tablespoon of something acidic, like apple cider vinegar to aid digestion) and then, in the morning, cook the mix, adding some salt (traditionally porridge was salty, not sweet), for 20 minutes, stirring regularly.

Medium oatmeal (often called Scottish oatmeal in the US)

These oats have been stoneground with the millstones set to create a medium meal.

Medium oatmeal was traditionally used for porridge in Scotland and in many other parts of the UK. It was also used in haggis, in puddings and sausages and as a coating when frying fish.

To make a traditional medium oatmeal porridge the Scottish way, bring water to the boil and, when it’s boiling, sprinkle in the medium oatmeal, stirring constantly. Once all of the oatmeal is incorporated, turn the pan down low, add salt (traditionally porridge was salty, not sweet) and simmer for 25 to 30 minutes, stirring regularly. To serve three people I use 180g medium oatmeal, 900g water and a half teaspoon salt.

Fine oatmeal

By stone-grinding the oat grains with the millstones more closely together, a fine oatmeal is produced.

Fine oatmeal was traditionally used for oatcakes – a savoury oat cracker – as well as a thickener for soups and stews.

Try my recipe for Naturally-Fermented Staffordshire Oatcakes which makes a delicious crêpe-like pancake or my Traditional Scottish Oatcakes recipe which will give you authentic Scottish oat crackers, great with soups or some cheese!

(If you want to try these two recipes and you don’t have fine oatmeal, don’t despair, they can easily be made with rolled oats too – follow the instructions in the recipes!)

Oats produced in steel mills:

In contrast to this traditional stone milling, most of the oats on our shelves today have been processed in modern steel mills. Here’s what you can find:

Steel Cut/Irish oats

Steel cut oats are so called because steel blades cut the whole groat into two or three pieces.

This type of oats are often called Irish oats in the US because the pieces are the same size as pinhead oatmeal, the type of oatmeal historically used to make porridge in Ireland.

In the kitchen, steel cut oats work in a similar way to their stone-ground cousin, pinhead oatmeal. If you want to make a traditional porridge with them, follow the instructions in the pinhead oatmeal section above.

Rolled Oats:

Rolled oats are so ubiquitous these days that one might think they’ve always been around. They are, however, a modern creation; the process of rolling oats only having been invented in 1877.

The Differences Between Rolled Oats and Oatmeal (link to article)

All rolled oats, whether large or small, are steam processed (for a second time, remembering they’ve already been steamed to prevent rancidity) before being rolled. This makes them softer and less likely to create dusty waste.

‘Old-fashioned’ Oats/Rolled Oats/Jumbo Oats

These, being the largest form of rolled oats, are whole oat grains that are re-steamed and run through roller mills to create large flakes.

These can be used to make a non-traditional (but very tasty!) porridge. There’s no need to soak them, cooking for 10-15 minutes on the stove does the job. If you’d like to serve traditionally, add salt during the cooking time.

I also have some traditionally-inspired recipes that use rolled oats! Try my cheesy oatcake-topped cottage pie or my sourdough oatcakes.

‘Quick Cook’ Rolled Oats

To make these smaller flaked oats, broken oat grains are re-steamed and put through roller mills.

These take just a few minutes on the stove to produce a porridge.

‘Instant’ Rolled Oats

These are the smallest, and hence the quickest cooking, form of rolled oats. They were brought to the oat market in 1966 by Quaker (who are now ownedi by Pepsi). Small pieces of oat grain are re-steamed and put through roller mills to create tiny, thin flakes.

I don’t think our ancestors would recognise instant oats (in texture or flavour). As a real food oat-lover, I’ve never used these.

The oat challenge:

If you’ve only ever used rolled oats, try something different this week. It’s easy to get hold of pinhead or steel cut oats – soak them before bed and take a few more moments in the kitchen to cook up your porridge the next morning. I think you’ll be surprised at how great it tastes!

Different Types of Oats – FAQs

Which type of oats is the healthiest?

Generally, the less a food is processed, the healthier it is. With this criteria, oat groats, that have had no further processing than their initial dehulling and stabilising are the healthiest.

But I am of the mind that the real food that you like is the healthiest. If you’re buying, cooking, and eating real food that you will like you’re more likely to continue with it – so choose the type of oat you like best.

How can I access stone-ground oats outside of the UK?

There are companies that import oats that have been stone-ground in the UK to other parts of the world. Check online to see if there’s one near you. In the US, Bob’s Red Mill sell a product called ‘Scottish oatmeal’ which is stoneground oats that are similar to British medium oatmeal.

Can I roll my own oats at home?

Yes you can! And they taste so much better rolled at home! Have a look at my article How to Roll Oats at Home (& 3 Good Reasons To Do It!).

Can I stone-grind my own oats at home?

It is possible to stone-grind oats from groats at home, but it is very difficult to replicate the pinhead/medium/fine grades of oatmeal that are available from large stone mills. This is because the stone mills use a number of sieves to sieve the meal into uniform sizes.

If you have a Mockmill, you can grind oats on any number above #3 (do not grind them on numbers #1 or #2 – the grain is too fatty and will clog up your meal). Using #3 or above will grind the oats but will give you a range of particle sizes from very fine dust to large chunks of oat groat. For making porridge this method works practically but does not replicate the porridge that you would make with uniform-sized commercially-produced oatmeal

How To Make Stone-Ground Oats in the Mockmill (link to article)

I love porridge/oatmeal. What else can I make with oats?

So many things! Here’s a selection of my traditional and traditionally-inspired recipes:

Naturally-Fermented Staffordshire Oatcakes

Cheesy oatcake-topped cottage pie

Sowans: The Scottish Oat Ferment

You can get three traditional oat recipes in my free download The Heritage Oat Collection. Enter your details below and I’ll send to your inbox:

I am currently in the process of writing a book to be called Oats: Recipes & Stories from the British Isles. It will include 50 recipes along with the stories of how this grain sustained many generations of people in the UK. Stay in touch via my newsletter (there is a sign up at the top of every page on this site) to hear the latest on this.

How can I make my oats healthier?

Fermenting your oats will unlock more nutrition and make them easier to digest. Learn how in my comprehensive article:

Is buying organic oats important?

I would always recommend buying organic oats. Choosing organic means that you are supporting farmers who care for our soil and our environment, stewarding it for the next generation. It also means that any residues left over from pesticides or fertilisers aren’t on your grains.

What are ‘naked’ oats?

‘Naked’ oats are a type of oat that, instead of having a hard difficult-to-detach hull, has a paper-thin hull. It is easier to prepare these grains for human consumption – it takes a lot of energy to remove the hard hull on standard oats; not as much energy is needed to remove the paper-thin hull on ‘naked’ oats.

Because these ‘naked’ oats do not have to go through a tough, damaging, process to remove their hulls, they are not heated before they get to our shelves. This results in a oat that is raw.

What are sprouted oats?

Sprouted oats are raw oats that have gone through a soaking and germination process to sprout them. This process is then halted by drying and the sprout knocked off. The sprouted groats can then be used as you would use a standard oat.

What are black oats?

Black oats are a type of oats that has a black hull. They were traditionally grown in large areas of Scandinavia and in Wales. Here are some I saw on a visit to Holden Farm in Wales:

What about oat flour?

What about oat flour?

Oat flour is a modern phenomenon which is finer than fine oatmeal. It can be purchased but can also be made from oatmeal or rolled oats by processing them in a high-powered coffee grinder or mixer.

You might also like:

The Difference Between Rolled Oats and Oatmeal

The Fascinating History of Jannock: The Giant Oat Bread That Defined Authenticity!

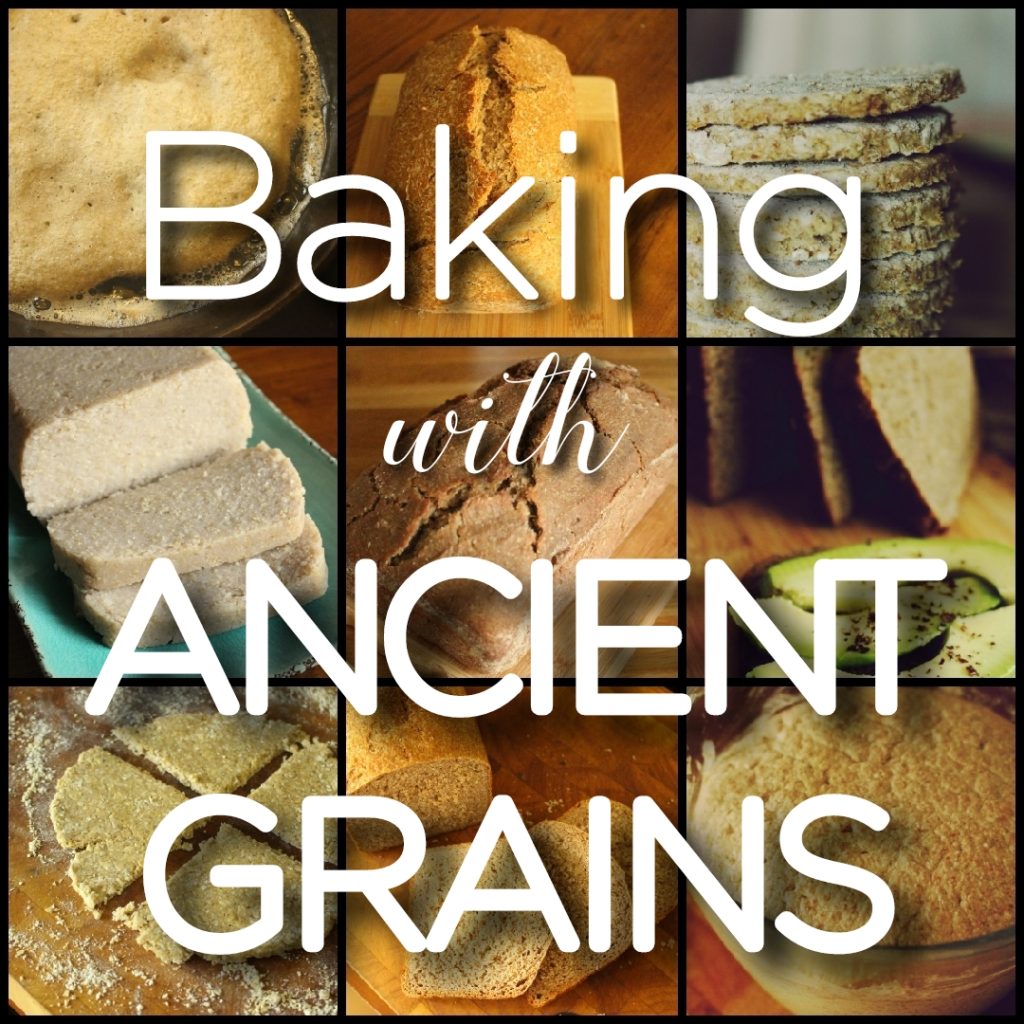

Bring ancient grain baking into your kitchen!

Download my free 30-page guide with five healthy and tasty 100% ancient grains recipes.

Love all the work you have done on researching oats, it is very comprehensive and I have not seen it all in one place as you have done here. Thank you.

Thanks Lizzy. I am glad it’s useful.

Hello, where do you buy all these different types of oats in the UK? And if Europe? Thank you so much!!

In the UK, I buy whole oats from Hodmedods and medium oatmeal and fine oatmeal from buywholefoodsonline.co.uk. When I lived in Italy, I was unable to get medium or fine oatmeal from any national source. I could buy Italian whole oat groats easily online though. I know you can get whole groats and medium oatmeal (often called steel-cut…but they are virtually identical) in most other European countries