“Jannock is scarcely ever seen in south east Lancashire now; but it used to be highly esteemed. The common expression “That’s noan jannock” applied to anything which is not what it ought to be, and commemorates the fame of this wholesome old cake”

Edwin Waugh, Sketches of Lancashire Life, 1855

“Can you rely on his support?” “Yes, lad, oi’m sartin he’s jonnock”

Notes and queries, 1882

Industrialisation, technological development and its partner, globalisation have led to not just a loss of culinary diversity; we’ve also, in parallel, lost so much linguistic uniqueness.

The oat bread called jannock, from the northern county of Lancashire in England, tells the story of both of these changes.

Many dictionaries, like the Oxford English Dictionary, include an entry for jannock which reads as follows:

“Jannock”: fair, genuine, straightforward.

And indeed jannock used to be a word in common parlance to describe something genuine. I have found it in transcriptions of speeches from the English parliament (it’s said to have been used by the famous Victorian Prime Minister, Gladstone) and it was part of the Lancashire dialect until very recently.

But jannock was an oat bread long before it was a way to describe something as fair or honest. It was the unadulterated qualities of jannock that prompted its transport into local vernacular. The bread was always made of oats and solely oats (unlike other breads that were often mixed with peas or beans). It could be relied on to be ‘the real deal’ and that motivated the communities that ate it to start referring to other things that were straightforward and honest as ‘jannock’.

The History of the Jannock

In 1327 the young English King Edward III came to the throne and needed a marriage that would help cement his political security. He chose the Flemish Philippa of Hainault (in Flanders, now Belgium) and they married in York.

Edward then invited communities from Philippa’s home to settle in the UK, and many of them came to Lancashire. It is said that they brought the jannock with them.

The first written mention of jannock is in the 1500s, as part of the text for the Chester Plays (a series of plays performed by the tradesmen of the city of Chester to illustrate stories from the Bible to the illiterate masses). It is then also included in other texts from the 1500 and 1600s, being defined in English, Latin, Dutch and Italian dictionaries as a loaf made solely of oatmeal.

What Was a Jannock?

The jannock was originally oats and water formed into a wide, circular, sloping loaf and baked. It was made in various sizes, some of them very big! In 1902 the jannock was reported as being 9 pounds in weight, 20 inches across, 4 inches in the centre sloping down to 1 inch at the side[1]. When we remember that the average large pizza is around 12 inches, we can grasp just how big the jannock could be!

The jannock became a favourite and staple food for working class communities in the early manufacturing towns of the area. The large circular breads were cut into slices called “thwacks” or “thwangs” that could easily be put in a pocket. This gave the bread a huge advantage over the other popular oat bread of the region; the thin, fragile havercake which “did not satisfy the appetite or offer the same staying power as the compact, fresh, sweet and at the same time soft conditioned, jannock”.

As a bread, jannock was made in many northern counties of the United Kingdom – but survived the longest in these Lancashire communities. It was still being made there at the turn of the 20th century (below you will see a picture of a jannock shop in Standishgate, Lancashire, 1889).

Recreating the Jannock

For a bread that was so renowned for being straightforward that it gave birth to its own adjective, recreating an authentic jannock is challenging! Though most original sources point to jannock being an unleavened bread made solely of oats, some define it sour (being made with buttermilk) and yet others, from a slightly later period, talk of it as a fruit loaf! It seems that, as with so many other regional recipes, each particular area made it their own and that, as dried fruit became more readily available and the advent of the home oven meant jannocks did not have to be made at the bakery, home cooks could add the luxury of fruit to this satisfying, simple loaf.

I have been unable to find any recipe or direction for how to make a jannock. Re-envisioning it in my own kitchen has seen me considering every word of the original quotes that I’ve found and much fun experimentation.

In my forthcoming book Oats: Stories & Recipes from The British Isles, I will share three recipes, one for an unleavened three-ingredient jannock, a second for a sourdough version and a third mixing in dried fruit for a sweeter option. Stay connected via my newsletter or Ancestral Kitchen Podcast to get news on the book!

Roeder, Charles. Notes on Food and Drink in Lancashire and Other Northern Counties, 1902. ↑

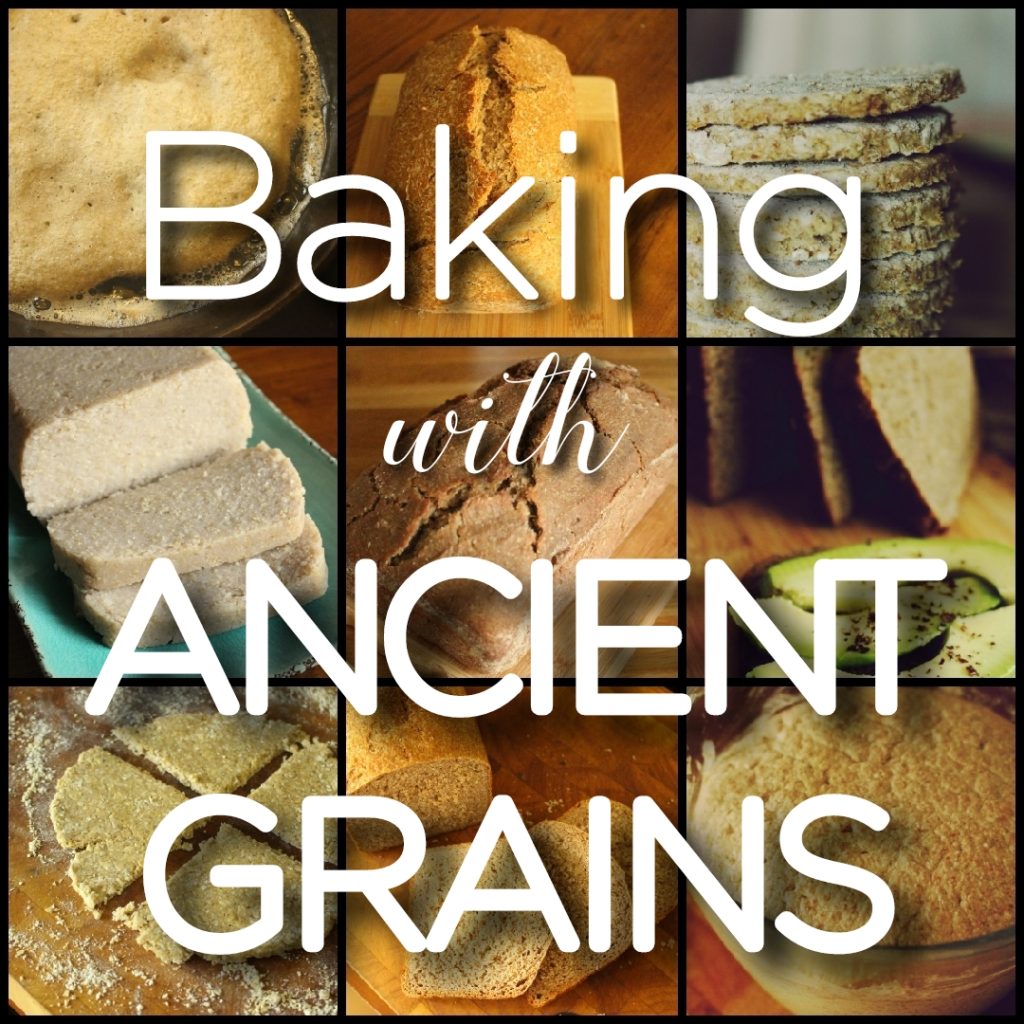

Bring ancient grain baking into your kitchen!

Download my free 30-page guide with five healthy and tasty 100% ancient grains recipes.

What a wonderful read! Absolutely facinating. I love the connection to ancestry and history that I feel when learning about the origins of foods. And from such simple, wholesome ingredients – makes me appreciate simplicity and frugalism in general. I look forward to your cookbook!

p.s. I made your fermented Christmas oat biscuits a few months ago. Delicious. I will make them again!

Hi Erica. Thank you for your note – yes, such simplicity born from necessity 🙂 I’m glad you enjoyed the long-fermented oat biscuits too!

Hi Alison,

Where can I find your book? I am interested in your recipes, especially the one for Jannock

Hi Becky,

Thanks for your interest! I am still in the process of writing it. I have done about 30% and have approached a publisher. It will be a few years yet. In the meantime, if you are on my newsletter, you’ll get updates on my progress plus regular recipes. You can sign up at the top of any page here on my site.

This was a lovely read and I really look forward to your book. is it possible to sign up for a newsletter so not to miss it when it comes?

Thank you Lisa! Yes, you can sign up for my newsletter.

If you’d like my newsletter plus my PDF download ‘The Heritage Oat Collection’ with 3 traditional British recipes, you can sign up here: https://ancestralkitchen.com/heritageoats/

If you don’t want the download, you can go to the top of any page on my site and pop your details in for the newsletter alone.

Alison