If I say the word beer, what do you think of?

For me, it’s that men drink it, and it tastes bitter.

Because of these two things, for most of my life I’ve thought beer wasn’t for me. Beer’s a man thing, right?! And the stuff they sell on the supermarket shelf tastes pretty awful!

Are you the same?

So what if I told you that, throughout history, beer brewing has most often been the woman’s job? And that, up to a few hundred years ago it didn’t taste bitter?

Women brewing beer? Yes, historically beer has been predominantly a woman’s domain.

Not bitter? No; the bittering agent added to modern beer, hops, was not regularly used in alcoholic drinks (certainly in the UK) until well in to the 17th century.

My journey to ancestral beers and ales has, over the last few years, revealed the incredible history of this drink. It has also taught me many things about fermentation and chemistry, along with giving me many batches of kitchen-brewed beer that have been a joy to learn through!

Where it all began – a 5,000-year old beer

I love fermenting. It started with sauerkraut over a decade ago and has since expanded into a kitchen full of bubbling things and a fascination with fermenting grains. I love sourdough bread, I regularly recreate the ancestral Turkish millet drink, boza, in my kitchen; I eat fermented porridge for breakfast most days. So when I came across a recipe in Sandor Katz’s book Wild Fermentation for a 5,000 year-old Egyptian beer called bouza; I knew I had to give it a go!

The process of making bouza goes something like this:

Soak a large amount of whole grains. Lightly break up half of these in a food processor and mix them with sourdough starter before shaping them into small loaves and par-baking them in a warm oven. Sprout the other half of the soaked grains, making them into malt.

Heat water for the brew and pour it into a simple fermentation vessel. Use the food processor again to lightly break apart your fresh malt, and also crumble up the par-baked loaves before adding both to the water. Let this mix come to room temperature, then add sourdough starter and stir well. Cover and leave this to ferment for several days.

Once the active fermentation seems to have slowed, strain the brew through a sieve to remove the grain (which I use to make bread!). You can now drink your cloudy, thick and sour bouza. Or, as I usually do, you can pour it into swing top bottles, add a spoonful of honey and some spices and leave it to ferment for another day, during which time it will lightly carbonate.

Modern home-brew v. 5,000 year-old bouza

There are many people around the world brewing their own beer today. But they aren’t doing it bouza-style. In fact, the process I’ve just described is worlds away from what a modern homebrewer would do to make beer.

Here are just some of the differences:

Modern home brewing…

- Uses chemically-sanitised vessels that are closed – designed to keep out ‘unwanted’ bacteria.

- Uses industrially-made dried malt, or even a jar of syrup made from malt in a factory.

- A sugary liquid (called wort) is made of this malt or malt syrup and that clear liquid is fermented.

- A yeast strain that has been cultured in a laboratory is used.

- Hops are added to sanitise and bitter the brew.

Bouza…

- Uses clean but unsanitised vessels that are open to the air during the fermentation process.

- Uses whole grains that are malted/processed at home.

- All of these grains go into the fermentation and stay in the fermentation until it’s complete.

- A homemade sourdough starter is used for culturing.

As you can see, aside from the fact that both these drinks use grain and are both fermented, they are very different! In the 5000 years between bouza-making and our modern concept of beer virtually everything in the processing has changed.

So how did pre-industrial beer-making look?

I am English, and my curiosity has led me to research pre-industrial drinks in England. Therefore the information in this article pertains to how English drinks were made. There are, however, a lot of similarities between English processes and how fermented grain drinks were made throughout the world before industrialisation.

First things first, pre-industrial beer was not actually beer; it was ale. Although these two words are used interchangeably in the modern world they actually denote two different drinks. Ale is the older of the two, and was made without the use of hops. Beer came onto the scene, at least in England, from the late 15th century with the inclusion of hops in the drink.

The introduction of hops, which came to England from the continent, are vital in the history of ale and beer because they sanitised the drink, enabling it to last longer. Prior to their introduction, ale would sour quickly, only lasting a few days. This meant it could not be transported very far or sold on an industrial scale.

Pre-industrial grain fermentation for drinks was done without hops. The result was ale (which is what I’ll refer to it as from now on in this article). Because it well did not keep well, it was made regularly. And this making was done by women. Brewing was a household task, just like making bread was. Women would make it in their kitchens every week. It was literally household knowledge; women learnt, at apron–strings, from their mothers and grandmothers how to brew.

Malt was made at home. This was then mixed with water in a large ‘tun’ (kettle/saucepan) brewed up over a fire to make a sugary wort to ferment. Then a household yeast, that was probably the same yeast used to make bread and certainly handed down and around by friends, was used to ferment that wort into ale. The fermenting vessels weren’t chemically sanitised and there was no way to keep air out of the ferment.

The ale was thicker, cloudier and less bitter than our modern beer. It also soured much more quickly than the beer on our supermarket shelves today.

Back to my brewing experiments

Making bouza, and holding a glass of home-made, 5,000-year old ale in your hands, is amazing! But it is very sour (I have read that bouza was originally sweetened by adding honey before serving) and quickly I realised I wanted to experiment with trying to change that. It was clear to me that a lot of the sourness was coming from the sourdough starter that I was using to start my ferment. Sourdough starter is a mix of yeasts and bacteria. Alcoholic drinks are usually cultured with yeasts alone, which produce alcohol as a by-product. Bacteria produce lactic and acetic acid and can make sour flavours.

I turned to my current fermenting practise to find yeast-based starters that I could swap out for the sourdough starter in the bouza recipe. I regularly make boza, a Turkish fermented millet drink and also the English drink mead, both of which I maintain yeast cultures for. I swapped out the sourdough starter in Sandor Katz’s recipe for a boza starter and for a mead starter and found that the resulting drink tasted less sour.

But it still became sour quite easily and quickly – this was due to the inclusion of airborne bacteria in the brew when it was fermenting.

Why don’t I just use commercial yeast?

At the same time as these experiments, I was reading up on medieval ale. I noticed that home brewers who are historical fans and reproduce medieval or traditional ales all use commercial yeast.

I can understand why – it’s easier! It introduces a laboratory-grown yeast into your ale which has literally been developed to produce a certain result. That reliable yeast helps in outnumbering any competing bacteria, making souring less likely.

I do not want to use commercial yeast.

I believe in the beauty, power and benefits of pre-industrial food and I do not want to use commercial yeast even though I know it provides more predictable results. Commercial yeast was developed in the 1880s off the back of Louis Pasteur’s discoveries in the 1850s. We’ve had it 150 years. Alcoholic drinks have been brewed for thousands and thousands of years (there is archaeological evidence dating back to the eighth century BC) – these people did not use commercial yeast.

The ale that British women made in their kitchens up and down the United Kingdom for hundreds and hundreds of years was made with a home-grown yeast population.

The risen breads that have been made by men and women since the the agricultural era (12,000 years ago) were, until 150 years ago, made with homegrown yeasts and bacteria.

The moving of our food out of our own hands, our own gardens, our own kitchens into laboratories and factories has shifted the raison d’etre of food production. It used to be about giving our bodies what they needed whilst looking after the local environment. It’s now about money. I believe this has ruined our society’s health and sanity. I respect the processes and wisdom of our ancestors. Therefore, I choose a diverse homegrown yeast culture for my ale.

If hops were used, it may be easier to get a good ale outcome from home-grown yeast cultures, because, after all, hops were introduced into brewing for their antibacterial properties. But because I choose not to use hops (partly because of wanting to recreate the beers my female ancestors made in their kitchens, and partly because I do not want to use hops which are soporific and oestrogenic), I have more of the challenge!

I have cultured yeast communities at home inspired by the description in Farmhouse Brewing by Lars Garshol, using rye flour, water, sugar (to encourage yeast), salt and rosemary (to discourage bacteria). I have also continued to experiment with the yeast culture that I make for the Turkish millet drink Boza.

Why don’t I use modern air-locked fermenting vessels?

Again, I could ‘help’ my process along (i.e. get a more reliably yeast-only brew that soured less quickly) if I used modern, specially-designed fermentation equipment (as most brewers of historical ale do). Aside from having a tiny kitchen and apartment and enough food equipment already, my female ancestors, just 400 years ago (and for centuries before that) brewed beer in their kitchens, using equipment that was not specialised. I want to explore and play with household, age-old process not follow along with developments created by science that have aided industrialised food production, so I choose to use household pots and pans; as women have done through the ages.

Moving towards medieval – more malt

Thanks to the work of people like Tofi Kerthjalfadsson (drawing on sources such as Judith Bennet’s brilliant book, Ale, Beer and Brewsters in England) I understood that the quantity of malt being used in medieval brews was substantially higher than that which I was using for my 5,000-year old bouza and also that medieval ale-makers dried their malt and then infused it in water, creating a sugary liquid, which, after staining the malt out, they fermented.

And this makes sense. More malt means more fermentable sugars, which means more alcohol. That alcohol helps kill off souring bacteria while still allowing alcohol-producing yeasts to thrive. And drying the malt means it can be stored and used whenever it’s needed.

In order to move my practice forwards, and try to replicate my medieval brewster ancestors, I started (as medieval brewsters would have) to dehydrate and subsequently create a sugar-infused liquid (called a wort) with my malt.

Where I’m at now

In my kitchen right now, I’m brewing ale with home-malted and dehydrated rye and (naked) oat grains. I make a wort with the dry malt and ferment with a robust home-made yeast culture from my ancient boza drink. You can read about my process in Becoming a Brewster – How I Make Medieval English Ale in my Kitchen.

If you would like to learn more, you can sign up for my newsletter at the top of this page, or listen to Ancestral Kitchen Podcast, where I often talk about my ale and, for patrons, I recently recorded a special episode on my brewing adventures. I would also love to hear from you at Alison (at) ancestralkitchen.com with questions or your own experiences with ancestral ale.

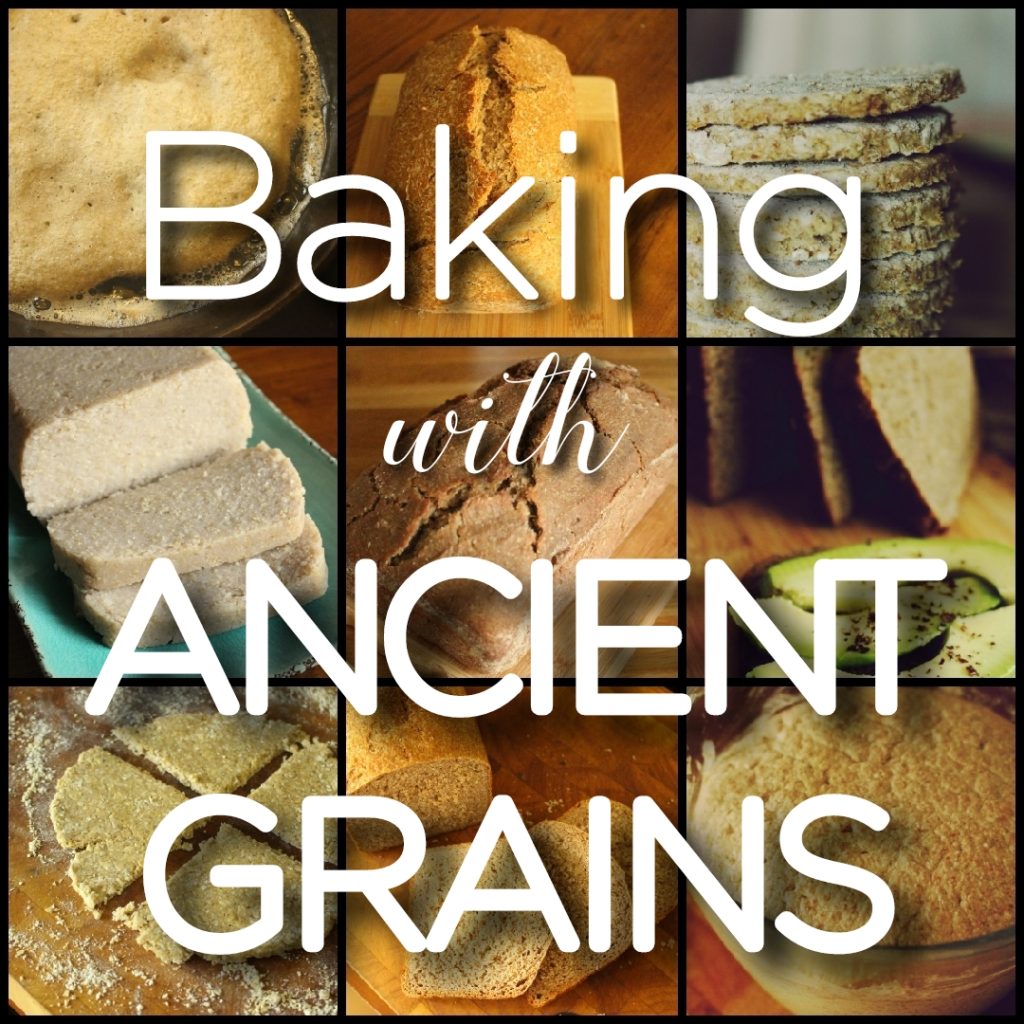

Bring ancient grain baking into your kitchen!

Download my free 30-page guide with five healthy and tasty 100% ancient grains recipes.

so excited to find your channel. I love the old health giving ways. I don’t want alcohol just good gut health. plus can’t wait to make the spent grain bread!!!

thanks for your experimentation and

sharing.

Hi Eva, I totally agree. The alcohol is a side benefit as it’s a completely different experience to alcohol as we know it 🙂

Fascinating stuff! I’ve been experimenting with variations on boza myself and I really enjoy it. My boza feels nourishing and lightly inebriating, whereas commercial beer feels like an unhealthy indulgence and is intoxicating. I will admit that laziness stops me from making boza as much as I’d like to. Another part of the problem is that there isn’t a ton of info out there (at least in English) on how to make such ancient fermented drinks properly, which is why I really appreciate coming across articles like this.

Cheers!

Hi George. I’m glad you’re enjoying Boza. I think it’s hard to know how to make these drinks ‘properly’, especially those (like Bouza and English medieval ale) that have died out but with research and application we can try our best to be faithful to our ancestors. Thanks for your comment 🙂

Just stumbled across this fascinating blog. Very very interesting article! Thanks for sharing!